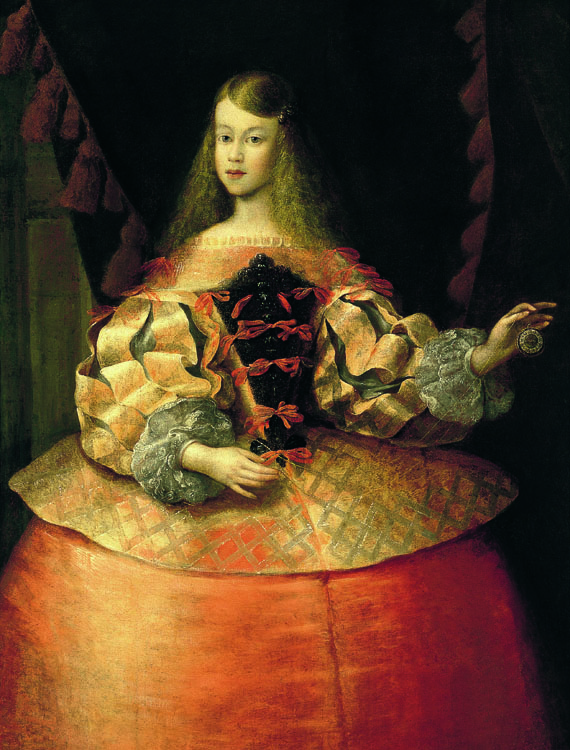

Step down into the astonishing underground gallery at the Yannick and Ben Jakober Foundation and you’ll find yourself surrounded by an extraordinary collection of portraits of extraordinary children. For many of the paintings here show little princes

and princesses foreordained to govern the destinies of their European subjects.

In many ways, this is a family reunion of sorts. Near the portrait of Spain’s Carlos II, aged just four, is the future king’s brother-in-law, baby Louis XIV of France, wrapped in swaddling. Louis’s mother and Carlos’s aunt, Anne of Austria is nearby, aged 13. Her other son, Philippe I Duc d’Orleans appears aged two and his English wife Henrietta is joined by her siblings James and the future King Charles. All three were orphaned by the axe at the fall of their father Charles I, who poses as a confident adolescent.

Perhaps such affinity explains the misshapen head and Hapsburg jaw of the aforementioned unfortunate Carlos, who suffered from ulcers, diseased bones and teeth and nervous disorders. Carlos’s condition, called mandibular prognathism, was the result of the very high degree of intermarriage between the various branches of the Habsburgs. There were multiple marriages of uncles and nieces, first cousins, nephews and aunts and, in the case of Spain’s Felipe II, all three.

Interesting as paediatric genetics are, though, there are plenty of other reasons to make your way to the Foundation. Down a bumpy dirt track in the hilly country past Alcúdia, it’s hard to get to. But you’ll find it’s even harder to leave. With sweeping views over the sea stands the wonderful Finca Sa Bassa Blanca. Designed by Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy in 1978 for sculptors Yannick and Ben Jakober, it boasts

exquisite latticed windows, delicate panelled ceilings and sturdy vaults and domes built around a fragrant Granadan-style courtyard. Originally a small Mallorcan farm, the property was a rundown military base until the 1970s and the new owners asked Fathy, then aged 78, to design a new building retaining only the outer walls.

The first portrait of what was to develop into an extraordinary collection had arrived on the scene a number of years before the house was finished, when in 1972, the couple acquired Girl with Cherries, a 19th-century painting by Mallorcan artist Juan Mestre. Gradually, over the decades, she was joined by 132 more portraits, with the focus of the collection shifting to 16th and 17th century portraiture.

“This selection enables us to follow the evolution of a certain way of depicting children as well as reflecting the metamorphosis of clothing,” says Ben Jakober of the collection, which is housed in a startling underground space, El Aljibe, a former water tank next to the house.

“There’s a slow evolution from an elegant austerity towards a frivolous exuberance. From the 19th century we can perceive a greater degree of expressiveness.”

Indeed, in the earlier portraits childhood doesn’t look like much fun at all. Dwarfed by their surroundings, standing stiffly and rigidly posed rather than at play, these are small adults mirroring future adult roles; they are the means to dynastic continuity.

You can see that these infants are destined for great things – they pose immobile, surrounded by symbols and props: sceptres, crowns, thrones and extravagant,

luxurious fabrics.

In the mid-18th century, though, there’s a shift in how children are viewed. Post Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the Enlightenment child is seen as a distinct social category, as inhabiting a world of extreme innocence. Visual representations of childhood reflect these changing views. Increasingly, spontaneous, realistic-looking children are shown outdoors, often at play, close to animals and part of a larger natural world.

And the great outdoors is something you emerge into after an hour or so in the subterranean gallery. The landscaped grounds of the finca are dotted with monumental sculptures by Ben, who is of Hungarian descent, and his French-born wife Yannick. It was Yannick who designed the rose garden, planted over the years with more than one hundred varieties of old and English roses and conceived as a mediaeval walled garden where the flowers grow alongside a herbarium of aromatic plants. But long after you have left the Finca Sa Bassa Blanca behind, it is the collection of children’s portraits that remains with you.

“It’s obvious that these princes and princesses experienced a childhood utterly different from what we understand today by that term,” says Ben. “But nevertheless, these faces, gazing out from the distant past, express perfectly the enigma and all-too fleeting nature of childhood.”

.