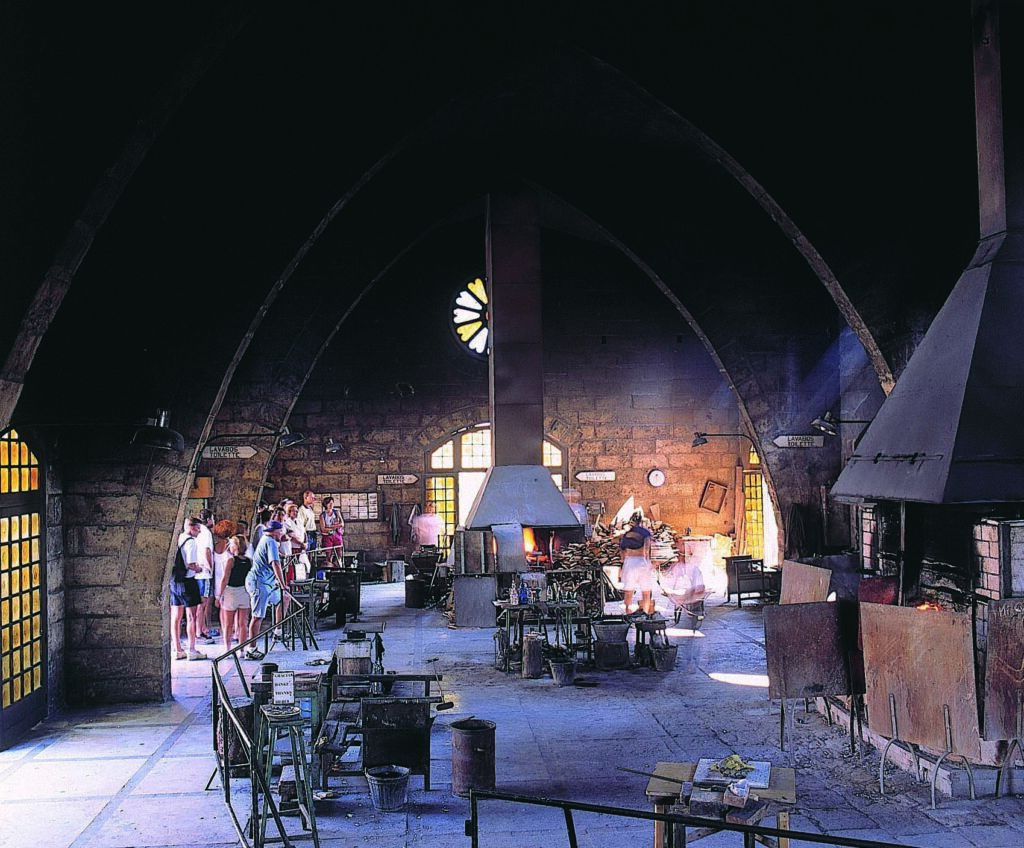

Even the bright lavalike glow is no match for the riot of flashbulbs as the young glassmaker, blowpipe in hand, swaggers away from the furnace and lights a cigarette from the dollop of molten glass. Elsewhere in the great vaulted hall of the faux castle, glassworkers stoke fires of 1300ºC, blow and twist glass, all under the gleeful gaze of jostling tourists gathered behind an iron rail.

“They’re well used to all the attention, of course,” explains Jesús Fernandez, general manager of the Gordiola Glassworks. “They crack jokes with the visitors, pose for photos and answer questions.”

Renaissance Venice, this is not. There, the feared Council of Ten dispatched murderous emissaries throughout Europe on behalf of the Serene Republic to eliminate runaway glassmakers lest they reveal Venice’s most closely guarded secret.

One shudders to think how the talkative Jesús would have fared back then.

“We send our team out all over Spain to hang the chandeliers, mostly in Madrid, Barcelona and Marbella,” he explains. And he goes on, revealing there are four furnaces, lit night and day, how the glassworks turns out between five and six thousand glasses a year and up to 300 chandeliers, and how they paint to order. “Company logos, that kind of thing.”

It’s a strong performer, you might say, for a family company. But the glassworks, founded in Palma in 1719, has always been ambitious in scope. The firm’s 1790 catalogue, for example, details “the chandeliers and lamps made by Master Gordiola to illuminate the palaces of Europe’s kings and those of other great lords of the Earth”.

Murano-style chandeliers in the Gordiola colors of green, blue, ruby, amethyst and turquoise are still the company’s most recognizable and interesting pieces.

The current factory complex, complete with “throne room”, trade show and conference pavilions, parking for 30 coaches and 100 cars, and a glass museum was built in 1975 by Daniel Aldeguer Gordiola.

An Indiana Jones-style archaeologist, Daniel, who died in 2008, spent most of his youth travelling the Middle East from one dig to another. Along the way he was kidnapped in Afghanistan – “I was mistaken for a CIA agent” – and machine-gunned from the air by Israeli fighter-planes while crossing the Syrian desert from Damascus to Palmyra.

“But,” he later recalled, “with the death of my uncle Bernardo in 1960, my travelling adventures, as he would call my research work, came to an end and I had to busy myself with the running of the glassworks.”

At that time the factory was located at La Portella, just inside Palma’s city walls to the east of the cathedral.

“But expansion was impossible and so, in 1969, I decided, with the approval of my uncle Gabriel, to move the glassworks out to the Manacor road.”

Over the next few years, he was to go considerably further – in the early 1970s he was invited to Iran to set up a glassworks and the furnace was lit at the Persian Gordiola Glass Company in 1973. Six years later, however, he and his Murano staff were forced to pack what they could, including glass destined for the ousted Shah’s palace, and beat a path to the Turkish border. “We didn’t stop until we reached Lake Van,” said Daniel.

The first glassmaking Gordiola, a Catalan glassware merchant, arrived in Mallorca in the early 18th century accompanied by an Aragonese glassmaker to set up shop together. A “dirty” white glass was produced, which, because the furnaces were not hot enough, tended to be frothy with tiny air bubbles trapped inside.

Gordiola’s son picked up some tricks of the trade in Murano, Venice, and by the mid-18th century the Palma glassworks were turning out Venetian-style chandeliers, though more austere and simpler than the originals.

But “great lords of the Earth” aren’t what they used to be and these days Gordiola’s biggest orders come from Spanish decorators and institutions such as the Paradores Nacionales chain of hotels. “And over the past 30 years,” says Jesus, “we’ve developed around 30 new designs. In our showroom you can see how we combine our different pieces of blown glass and how we apply fusing.”

As for the future, the company is determined to continue as it has done for almost 300 years. “We have to compete with other markets where production is carried out on an industrial scale and with molds,” says Jesus. “But we have a responsibility to safeguard the tradition of blown glass here in Mallorca.”

The Gordiola Glassworks and Museum: Crtra Palma-Manacor km 19, near Algaida. Open: Mon-Fri: 9am-6pm; Saturday: 9am-2pm. Closed Sunday.