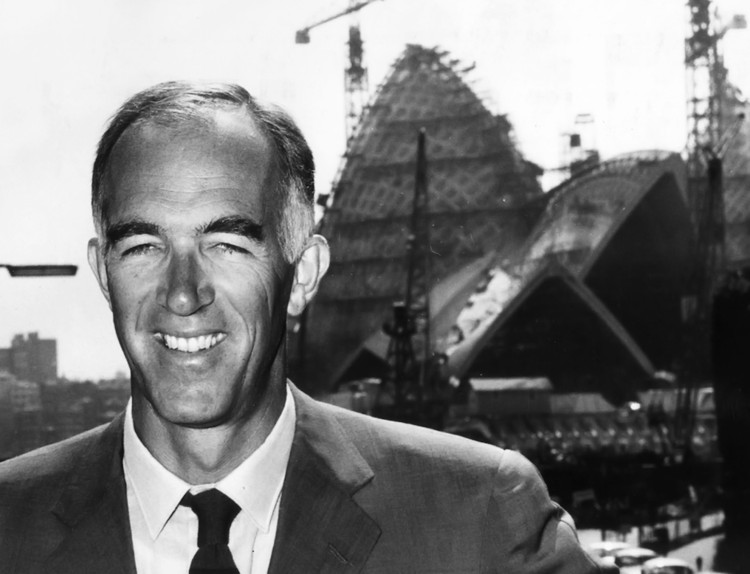

In Sydney he designed a building that has come to stand for a nation. Then Jørn Utzon, the architect of the iconic opera house, retreated to Mallorca where he built two sublime homes, both based around a series of inter-linked blocks. Drawing on African and Chinese forms, responding to terrain, landscape and climate, and using local materials, Utzon redefined contemporary Mediterranean architecture forever.

Utzon was visiting friends in Mallorca and was beguiled by the landscape and climate, which were not unlike New South Wales where he and his family had lived in the early 1960s. After enquiring of a local farmer if any land was for sale, they were offered three plots: “beautiful; marvellous; and paradise”.

Wisely, they chose paradise, located inland on a steep hill with sweeping views over farmland and far away to a distant, shimmering ribbon of sea. But the Utzons weren’t ready for paradise just yet and bought another plot, this one on a clifftop site overlooking the sea near Porto Petro. Here, in 1972, Utzon built Can Lis, a spectacular family home which, with its use of local materials and its eloquent response to site and climate, set the standard for contemporary Mediterranean architecture.

Set among pines and myrtles, Can Lis is staggered along the cliff top in five loosely linked blocks, each individually adjusting to the terrain and contours of the land. Initially modelled using sugar cubes, there’s a kitchen and dining block, with colonnaded outdoor eating and seating area, a separate living room, and two bedroom blocks, each with its own sitting court looking out to sea.

Utzon was pleased to find that a basic kit of parts was available locally. Firstly, his building blocks – traditional, buttery-coloured sandstone – were quarried nearby and sold in standard sizes of 80x40cm and either 10 or 20cm thick. The architect asked the stone masons to leave the rough circular saw marks on the stone. A different harder stone from Santanyi was used for the floors. To make roofs and the door and window openings, concrete I-beams were standard, and these beams were then spanned by local arched terracotta tiles.

“My father loved working with the local craftsmen,” recalled Utzon’s son Jan some 30 years later when he picked up the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize on his behalf. “When he appeared at the building site with some bottles of wine, the craftsmen knew that he’d had new ideas during the night and that some of the work already done would have to be changed.”

He must have run through the stuff by the crate load, because Utzon continually adjusted his original plans on site. While building the living room for instance, the masons ran out of stone, but it was agreed all round that the space had by then reached the right proportions.

As Utzon grew older, the glaring surface of the sea became too much for eyes weakened by a lifetime studying pencil drawings. What’s more, architectural pilgrims and sightseers were becoming a real nuisance. The Utzons decided to move inland and build on their “paradise” site. They called this house Can Feliz.

Here, the architect designed three blocks containing living, dining and bedroom spaces, set side by side. The tapered, funnel-like apertures of Can Lis have been replaced here by three deep bays formed by temple-like columns. Window bays are half the width as those at Can Lis, but twice the height. The result feels unmistakably Greek, a miniature Acropolis.

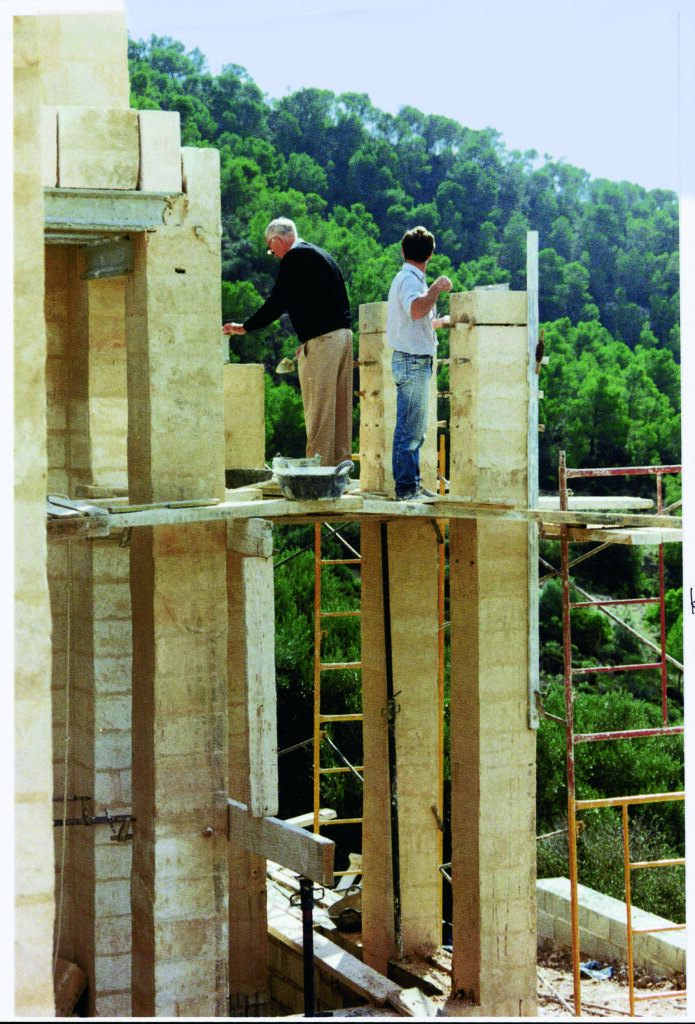

Once again Utzon used the same materials as Can Lis, but the rougher blocks have been tamed this time. And once again, Utzon took an active role in the construction process.

“He was on site the whole time. He came every day,” recalls architectural assistant Børge Nissen. It was fascinating for Nissen to work alongside Utzon, but he goes on, “in some ways it was quite boring for me too; I didn’t actually have to do any thinking. Utzon had everything already solved!”