In 1909, British paleontologist Dorothea Bate unearthed a creature unlike any the world had ever seen — a small, goat-like animal with strange, rodent-like teeth and forward-facing eyes. This remarkable discovery on the island of Mallorca introduced the world to the Myotragus balearicus, an extinct species that had once roamed this Balearic island. Bate’s discovery not only opened a window into the prehistoric world of the Mediterranean, but it also cemented her legacy as a pioneering female scientist in an era when few women worked in the field.

Bate, born in Wales in 1878, was a trailblazer in archaeozoology. She dedicated her career to uncovering fossils of recently extinct mammals, aiming to understand the evolution of giant and dwarf species and the factors driving these transformations.

Bate’s fascination with fossils and her self-taught expertise led her to the Mallorca, where she became one of the first scientists to explore the region’s unique prehistoric fauna. She had begun her career at the British Museum, making a name for herself with her meticulous research and ability to find extraordinary fossils in often-overlooked places, such as Crete and Cyprus. In Mallorca, she was particularly drawn to the mysterious limestone caves, where she hoped to discover the remains of ancient animals that had lived in isolation on the island for millennia.

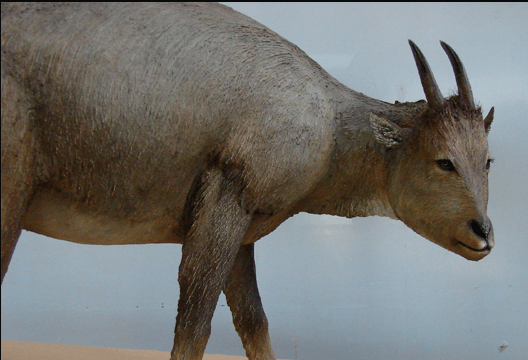

Her perseverance paid off when she discovered the remains of the Myotragus, a species that had adapted to life on the isolated island in fascinating ways. The Myotragus was a dwarf goat, just half the size of a modern goat, with some features that resembled a rodent. It is estimated to have been approximately 50 centimeters (1.6 ft) tall at the shoulder, and had an estimated adult body mass of around 23–32 kg (51–71 lb).

Its forward-facing eyes, an unusual trait for herbivores, suggested it had poor peripheral vision. The animal’s teeth were another peculiar feature: its incisors continuously grew, much like those of rodents, indicating that the Myotragus likely grazed on tough, fibrous vegetation.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Myotragus was its evolutionary adaptation to life without predators, which allowed the species to evolve with minimal need for speed or defense. As a result, Myotragus had a relatively slow metabolism and moved sluggishly compared to other herbivores. It was a perfect example of island dwarfism, a phenomenon where species confined to isolated environments evolve into smaller forms to conserve resources.

Dorothea Bate’s work on the Myotragus was groundbreaking not only for the discovery itself but also for what it revealed about evolution in isolated ecosystems. Her findings were ahead of their time, offering early insights into concepts that have become central to evolutionary biology today.

Bate’s legacy as a paleontologist is significant, not only because she was one of the first women to achieve prominence in a male-dominated field, but also because her discoveries expanded our understanding of island biogeography. Her pivotal work laid the foundation for much of what we know today about species adaptation on islands.

Although the Myotragus became extinct approximately 5,000 years ago, likely due to the arrival of humans on the islands, its story continues to fascinate scientists and enthusiasts alike. Dorothea Bate’s discovery remains one of Mallorca’s most exciting paleontological finds, and her work continues to inspire researchers exploring the unique evolutionary paths of island species.

Photo: Flickr