It’s the turn of the century and the sturdy bourgeoisie of Sóller are busy. Thanks to a burgeoning trade in oranges, they’ve got French money and perhaps, more importantly, French ideas. Already Gran Via, a magnificent avenue lined with imposing townhouses and villas, decorated with wrought iron, is taking shape. Not merely thoroughly modern but thoroughly modernista to boot, the taste for Art Nouveau in the growing town is insatiable.

But high above the bustling lanes, streets and squares, stonemasons and sculptors are diligently at work too. For here, on a series of imposing terraces, planted with cypress trees, pines and palms, and with sweeping views across the mountains and down to the sea, the Sollerics are preparing a city for their dead.

The picturesque graveyard in nearby Deià boasts the tomb of poet and writer Robert Graves – who wrote that the church is believed to have been built on an ancient temple to the moon goddess. It was a place, he said, that reverberated with magic. The Sollerics, practical moneymaking folk, make no such claims for their own cemetery. Nevertheless, it’s in the cemetery of Sóller not Deià, where the visitor feels most intimately a communion with the dead.

𝗧𝗮𝗸𝗲𝗻 𝗳𝗿𝗼𝗺 𝗹𝗶𝗳𝗲

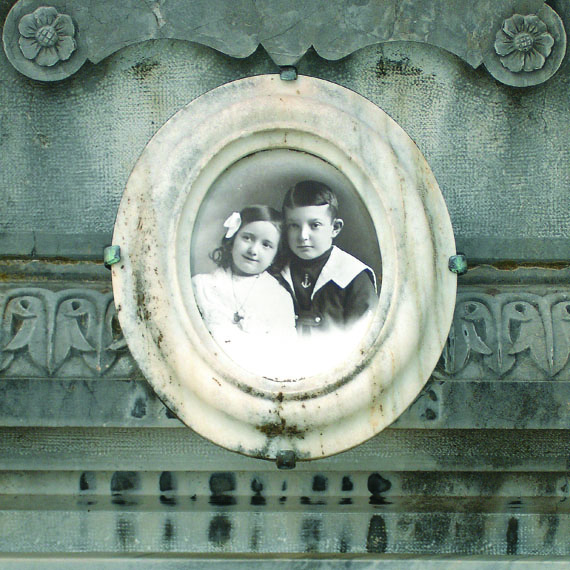

There are the photographs on the tombs, for one. From almost every tomb, from the simplest to the most monumental, in faded black and white and 1970s Kodak color, the dead are there to be seen. It would be superstitious to countenance that they observe us. Rather, we watch them, imagining their long-finished lives, a funeral procession of archetypes: the solid mustachioed burgher, the stoney-faced spinster, the 1930s matinee idol, the winsome bride, the grinning baby, the cocksure youth. Their graves are adorned with intricate wrought-iron candelabra and flowers – real, plastic and, strikingly, in brightly coloured ceramic.

Soller began systematically burying its dead here in 1814, with the parish priest exhorting the faithful to dedicate their free time to construction work. Over the years the cemetery was to expand – in 1900, 1913, 1932, 1963 and 1989 – and today the tombs are distributed over three terraces with the latest addition further below and off to one side. The first and second levels are connected by a stairway which gives way to a plaza and, throughout, there are pine and cypress trees, making Soller’s cemetery one of the lushest on the island.

𝗔 𝗿𝗮𝗴𝗲 𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗻𝗲𝘄

Then there are the tombs themselves. Even as the Sollerics were busy building their Art Nouveau townhouses below, they were preparing Art Nouveau graves for their loved ones and themselves above. But it’s Nouveau with a new, local, twist. Mallorcan modernisme is like the island itself, a promiscuous mix of influences. From Barcelona come the florid touches, the exaggerated organic Gaudiesque signature, from Austria the lines and geometry of the Secession movement, from France and Belgium, rational ornamentation.

Angels are pre-Raphaelite, innocent, feminine, human. Rather than swooping through the cemetery as legions of trumpet-blowing heralds of Final Judgment, they move quietly among us, conveying intimate, inconsolable grief, irreparable loss, and enduring pain. Others suggest private hope that a loved one will be taken into the bosom of God. There’s potent symbolism – floral motifs, skulls, bats and incense burners. And there are touching epitaphs: in Catalan, Spanish, French, Latin and English, ranging from the oratorical– “Oh Christ, our only hope” – to the ordinary: “In memory of a most loving mother”.

𝗔 𝗺𝗼𝗻𝘂𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁𝗮𝗹 𝘂𝗻𝗱𝗲𝗿𝘁𝗮𝗸𝗶𝗻𝗴

In 1918 the Morrell i Coll family commissioned a marble set piece from Barcelona sculptor Josep Llimona Bruguera. It stands out for the very reason it shouldn’t. For among the towering crosses, baldachins and obelisks, this one sits squarely at eye level. The naturalistic figures of the dead Christ, the mourning Magdalene, St John and a female figure symbolizing grief reward a view from any number of angles, unlike the monolithic angels nearby. Sentimental it may seem, but that no doubt was Llimona’s intention: to manifest human sentiment in stone through an iconic image, which though a picture of desolation, holds out the hope of resurrection.

Less expressive are the figures by Llimona’s student, Palma-born Miquel Arcas i Pons. Here we find distant, immutable, free-standing angels on high pedestals. But though they fail to communicate the same sheer terror of loss or joyfulness of hope, they come, nevertheless bearing messages. One holds open a book with the inscription “Thou shalt not die but live eternally”; another holds a garland of flowers symbolizing repetition, regeneration.

More austere are the communal mausoleums. Here, stacked five high in plain niches, rest the more recent Soller dead, their photographs pinned to the slabs, a mechanized crane hanging above to facilitate their burial.

And below in the valley of Soller modern blocks of homes, stacked five high, await a new generation of Sollerics.